TAEN: A Model-Constrained Tikhonov Autoencoder Network for Forward and Inverse Problems

Paper publication

Publication Link: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0045782525005171

Citation:

@article{van2025taen,

title={TAEN: a model-constrained Tikhonov autoencoder network for forward and inverse problems},

author={Van Nguyen, Hai and Bui-Thanh, Tan and Dawson, Clint},

journal={Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering},

volume={446},

pages={118245},

year={2025},

publisher={Elsevier}

}

Table of Contents

- Paper publication

- Table of Contents

- Objectives

- Significant Results

- Methodology

- Problem 1: 2D Heat Equation

- Problem 2: 2D Navier-Stokes Equations

- Training Cost and Speedup with Deep Learning Solutions

Objectives

Efficient real-time solvers for forward and inverse problems are essential in engineering and science applications. Machine learning surrogate models have emerged as promising alternatives to traditional methods, offering substantially reduced computational time. Nevertheless, these models typically demand extensive training datasets to achieve robust generalization across diverse scenarios. While physics-based approaches can partially mitigate this data dependency and ensure physics-interpretable solutions, addressing scarce data regimes remains a challenge. Both purely data-driven and physics-based machine learning approaches demonstrate severe overfitting issues when trained with insufficient data.

We propose a novel model-constrained Tikhonov autoencoder neural network framework, called TAEN, capable of learning both forward and inverse surrogate models using a single arbitrary observational sample. We develop comprehensive theoretical foundations including forward and inverse inference error bounds for the proposed approach for linear cases. For comparative analysis, we derive equivalent formulations for pure data-driven and model-constrained approach counterparts. At the heart of our approach is a data randomization strategy with theoretical justification, which functions as a generative mechanism for exploring the training data space, enabling effective training of both forward and inverse surrogate models even with a single observation, while regularizing the learning process. We validate our approach through extensive numerical experiments on two challenging inverse problems: 2D heat conductivity inversion and initial condition reconstruction for time-dependent 2D Navier-Stokes equations. Results demonstrate that TAEN achieves accuracy comparable to traditional Tikhonov solvers and numerical forward solvers for both inverse and forward problems, respectively, while delivering orders of magnitude computational speedups.

Significant Results

Methodology

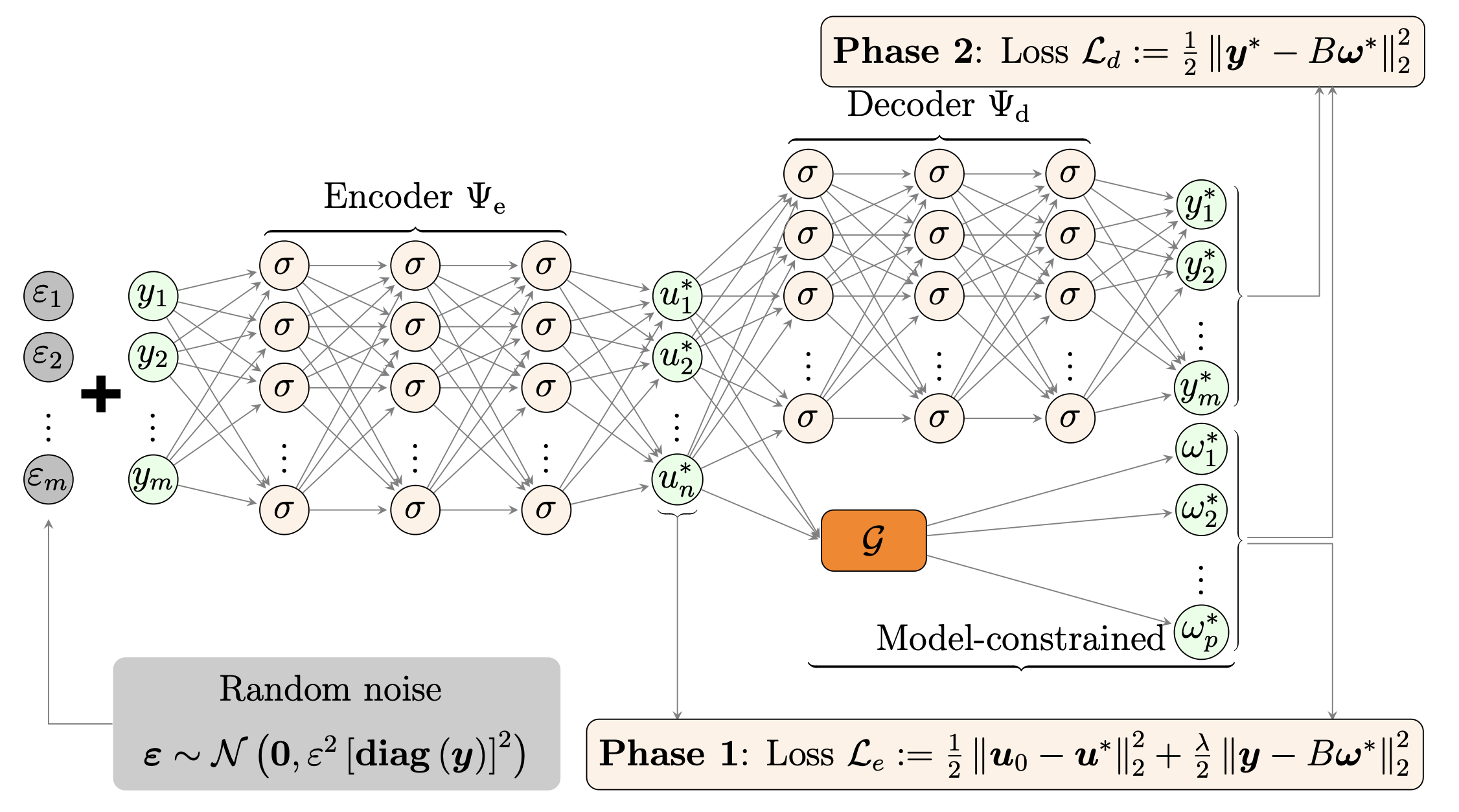

The TAEN framework employs a model-constrained autoencoder architecture that learns both forward and inverse mappings simultaneously. The key innovation is the integration of Tikhonov regularization principles with data randomization techniques and using the physics model to constrain the neural networks, enabling effective learning from minimal training data.

Loss Functions for Different Approaches:

We compare several autoencoder approaches for learning forward and inverse mappings. Here are the key loss functions:

- Pure POP (Purely data-driven Parameter-to-Observable-to-Parameter):

- Encoder: \(\min \frac{1}{2} \|\Psi_e(\mathbf{P}) - \mathbf{Y}\|_F^2\)

- Decoder: \(\min \frac{1}{2} \|\Psi_d(\Psi_e^*(\mathbf{P})) - \mathbf{P}\|_F^2\)

- Pure OPO (Purely data-driven Observable-to-Parameter-to-Observable):

- Encoder: \(\min \frac{1}{2} \|\Psi_e(\mathbf{Y}) - \mathbf{P}\|_F^2\)

- Decoder: \(\min \frac{1}{2} \|\Psi_d(\Psi_e^*(\mathbf{Y})) - \mathbf{Y}\|_F^2\)

- mcPOP (Model-constrained Parameter-to-Observable-to-Parameter):

- Encoder: \(\min \frac{1}{2} \|\Psi_e(\mathbf{P}) - \mathbf{Y}\|_F^2\)

- Decoder: \(\min \frac{1}{2} \|\Psi_d(\Psi_e^*(\mathbf{P})) - \mathbf{P}\|_F^2 + \frac{\lambda}{2} \|\mathbf{B} \circ \mathcal{F}(\Psi_d(\Psi_e^*(\mathbf{P}))) - \mathbf{Y}\|_F^2\)

- mcOPO (Model-constrained Observable-to-Parameter-to-Observable):

- Encoder: \(\min \frac{1}{2} \|\Psi_e(\mathbf{Y}) - \mathbf{U}\|_F^2 + \frac{\lambda}{2} \|\mathbf{B} \circ \mathcal{F}(\Psi_e(\mathbf{Y})) - \mathbf{Y}\|_F^2\)

- Decoder: \(\min \frac{1}{2} \|\Psi_d(\Psi_e^*(\mathbf{Y})) - \mathbf{B} \circ \mathcal{F}(\Psi_e^*(\mathbf{Y}))\|_F^2\)

- mcOPOfull (Model-constrained Observable-to-Parameter-to-Forward):

- Encoder: \(\min \frac{1}{2} \|\mathbf{U} - \Psi_e(\mathbf{Y})\|_F^2 + \frac{\lambda}{2} \|\mathbf{Y} - \mathbf{B} \circ \mathcal{F}(\Psi_e(\mathbf{Y}))\|_F^2\)

- Decoder: \(\min \frac{1}{2} \|\mathcal{F}(\Psi_e^*(\mathbf{Y})) - \Psi_d(\Psi_e^*(\mathbf{Y}))\|_F^2\)

- TAEN (Tikhonov Autoencoder Network):

- Encoder: \(\min \frac{1}{2} \|\Psi_e(\mathbf{Y}) - \mathbf{u}_0 \mathbf{1}^T\|_F^2 + \frac{\lambda}{2} \|\mathbf{B} \circ \mathcal{F}(\Psi_e(\mathbf{Y})) - \mathbf{Y}\|_F^2\)

- Decoder: \(\min \frac{1}{2} \|\Psi_d(\Psi_e^*(\mathbf{Y})) - \mathbf{B} \circ \mathcal{F}(\Psi_e^*(\mathbf{Y}))\|_F^2\)

- TAENfull (Tikhonov Autoencoder Network - Full Forward Map):

- Encoder: \(\min \frac{1}{2} \|\Psi_e(\mathbf{Y}) - \mathbf{u}_0 \mathbf{1}^T\|_F^2 + \frac{\lambda}{2} \|\mathbf{B} \circ \mathcal{F}(\Psi_e(\mathbf{Y})) - \mathbf{Y}\|_F^2\)

- Decoder: \(\min \frac{1}{2} \|\mathcal{F}(\Psi_e^*(\mathbf{Y})) - \Psi_d(\Psi_e^*(\mathbf{Y}))\|_F^2\)

where \(\Psi_e\) and \(\Psi_d\) are encoder and decoder networks, \(\mathbf{P}\) and \(\mathbf{Y}\) are training parameter and observation data, \(\mathcal{F}\) is the forward model (PDE solver), \(\mathbf{B}\) is the observation operator, \(\lambda\) is the regularization parameter, and \(\mathbf{u}_0\) is the prior mean of parameters. The key difference of TAEN is that it uses \(\mathbf{u}_0\) instead of ground truth parameters \(\mathbf{P}\), enabling learning from a single observation sample.

Problem 1: 2D Heat Equation

We investigate the following heat equation:

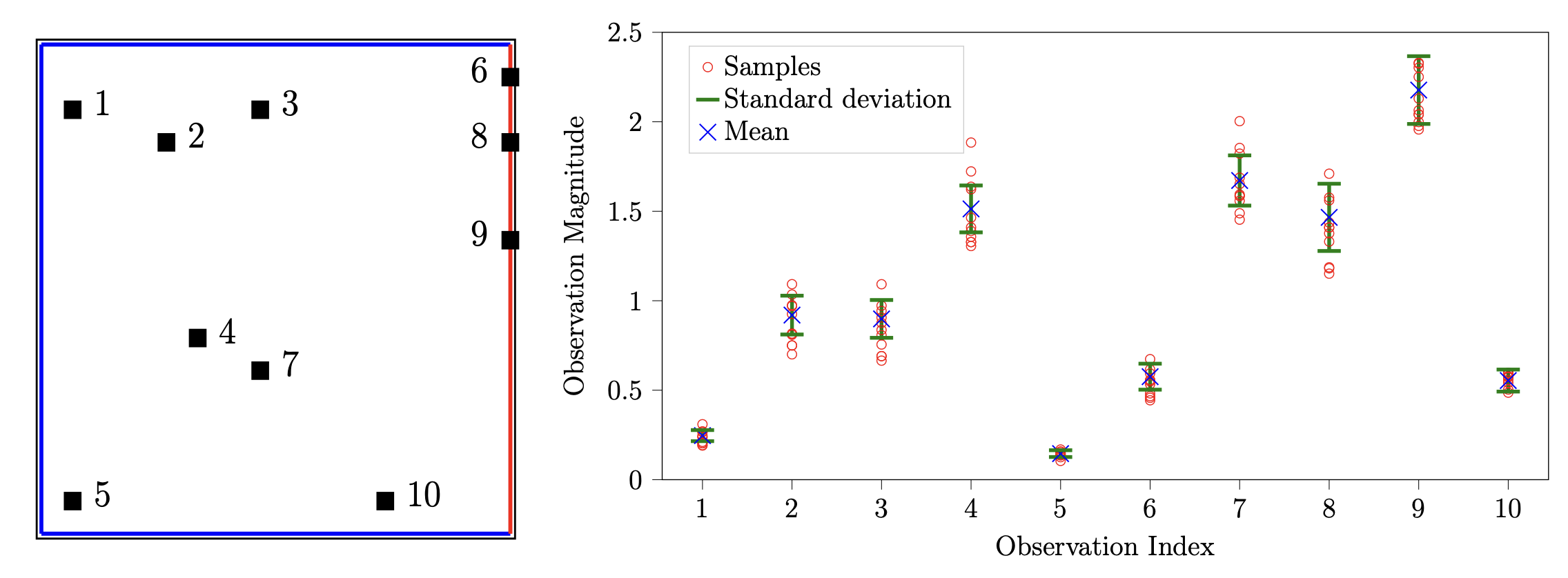

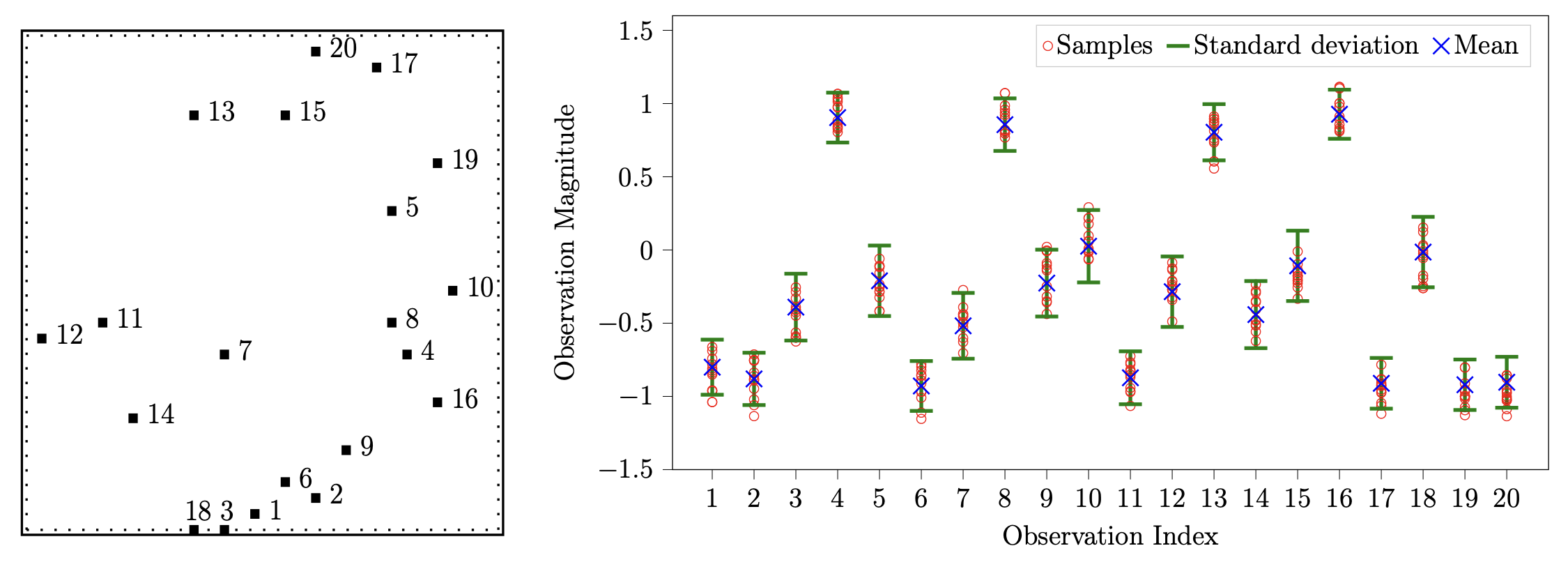

\[\begin{align*} -\nabla \cdot (e^u \nabla \omega) & = 20 \quad \text{in } \Omega = (0,1)^2 \\ \omega & = 0 \quad \text{ on } \Gamma^{\text{ext}} \\ \textbf{n} \cdot (e^u \nabla \omega) & = 0 \quad \text{ on } \Gamma^{\text{root}}, \end{align*}\]where \(u\) represents the (log) conductivity coefficient field (the parameter of interest PoI), \(\omega\) denotes the temperature field, and \(\textbf{n}\) is the unit outward normal vector along the Neumann boundary \(\Gamma^{\text{root}}\). As illustrated in the left panel of Figure 2, we discretize the domain using a \(16 \times 16\) grid, with 10 randomly distributed observation points sampling from the discretized field \(\mathbf{y}_{\text{full}}\).

We aim to achieve two primary goals: (1) learning an inverse mapping to directly reconstruct the conductivity coefficient field \(\mathbf{u}\) from 10 discrete observations \(\mathbf{y} = \mathbf{B} \mathbf{y}_{\text{full}}\), and (2) learning a PtO map or forward map that predicts either the temperature observations \(\mathbf{y}\) or the temperature field \(\mathbf{y}_{\text{full}}\) given a conductivity coefficient field \(\mathbf{u}\).

The following table summarizes the average relative error for inverse solutions and forward solutions (observations) over 500 test samples obtained by all approaches trained with {1,100} training samples. The model-constrained approaches are more accurate for both inverse (comparable to the Tikhonov—Tik—approach) and forward solution, and within the model-constrained approaches, TAEN and TAENfull are the most accurate ones: in fact one training sample is sufficient for these two methods.

| Approach | Inverse (%) (1 sample) | Forward (1 sample) | Inverse (%) (100 samples) | Forward (100 samples) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure POP | 100.18 | 3.99×10⁻¹ | 80.48 | 5.30×10⁻² |

| Pure OPO | 107.55 | 2.90×10⁻¹ | 50.18 | 1.09×10⁻¹ |

| mcPOP | 107.99 | 3.99×10⁻¹ | 87.60 | 5.30×10⁻² |

| mcOPO | 108.28 | 2.73×10⁻² | 46.32 | 3.94×10⁻⁴ |

| mcOPOfull | 108.28 | 4.21×10⁻² | 46.32 | 4.56×10⁻⁴ |

| TAEN | 45.23 | 1.57×10⁻⁴ | 45.03 | 1.22×10⁻⁴ |

| TAENfull | 45.23 | 8.80×10⁻⁴ | 45.03 | 2.12×10⁻⁴ |

| Tikhonov | 44.99 | - | 44.99 | - |

Table 1: 2D heat equation. The average relative error for inverse solutions and forward solutions (observations) over 500 test samples obtained by all approaches trained with {1,100} training samples. The model-constrained approaches are more accurate for both inverse (comparable to the Tikhonov—Tik—approach) and forward solution, and within the model-constrained approaches, TAEN and TAENfull are the most accurate ones: in fact one training sample is sufficient for these two methods. We compare all approaches using the aforementioned two-phase sequential training protocol. All methods are implemented under two scenarios: training with a single training sample and training with 100 training samples. For mcOPO, mcOPOfull, TAEN, and TAENfull approaches, we perform data randomization for each epoch by adding random noise with magnitude \(\epsilon = 10\%\) to the already-noise-corrupted observation samples.

Generating train and test data sets.

We start with drawing the parameter conductivity samples via a truncated Karhunen-Loève expansion

\[u(x) = \sum_{i =1 }^q \sqrt{\lambda_i} \boldsymbol{\phi}_i(x) \mathbf{u}_i, \quad x \in [0,1]^2,\]where \((\lambda_i, \boldsymbol{\phi}_i)\) is the eigenpair of a two-point correlation function, and \(\mathbf{u} = \{\mathbf{u}_i\}_{i=1}^q \sim \mathcal{N}(0,\mathbf{I})\) is a standard Gaussian random vector. We choose \(q = 15\) eigenvectors corresponding to the first \(15\) largest eigenvalues. For each sample \(\mathbf{u}\), we solve the heat equation for the corresponding temperature field \(\mathbf{y}_{\text{full}}\) by the finite element method. The observation samples \(\mathbf{y}^{\text{clean}}\) are constructed by extracting values of the temperature field \(\mathbf{y}_{\text{full}}\) at the 10 observable locations, followed by the addition of Gaussian noise with the noise level of \(\delta = 0.5\%\). Our training dataset consists of 100 independently drawn sample pairs. For the inference (testing) step, we generate 500 independently drawn pairs \((\mathbf{u}, \mathbf{y}_{\text{full}})\) following the same procedure discussed above.

Learned inverse and PtO/forward maps accuracy.

| Approach |

1 training sample mean |

1 training sample std |

100 training samples mean |

100 training samples std |

| Pure POP |

|

|

|

|

| Pure OPO |

|

|

|

|

| mcPOP |

|

|

|

|

| mcOPO / mcOPOfull |

|

|

|

|

| TAEN / TAENfull |

|

|

|

|

| Tik |

|

|

| Pure POP / mcPOP | Pure OPO | mcOPO | mcOPOfull | TAEN | TAENfull | |

| 1 sample |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 100 samples |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 training sample mean |

1 training sample std |

100 training samples mean |

100 training samples std |

|

| mcOPOfull |

|

|

|

|

| TAENfull |

|

|

|

|

| $$\mathbf{u}_\text{Tik}$$ | $$\mathbf{u}_{\text{TAENfull}}$$ | $$\mathbf{u}_\text{True}$$ | $$\mathbf{y}_{\text{TAENfull}}$$ |

|

|

|

|

|

| $$\|\mathbf{u}_\text{Tik} - \mathbf{u}_\text{True}\|$$ | $$\|\mathbf{u}_{\text{TAENfull}} - \mathbf{u}_\text{True}\|$$ | $$\mathbf{y}_\text{True}$$ | $$\|\mathbf{y}_{\text{TAENfull}} - \mathbf{y}_\text{True}\|$$ |

|

|

|

|

|

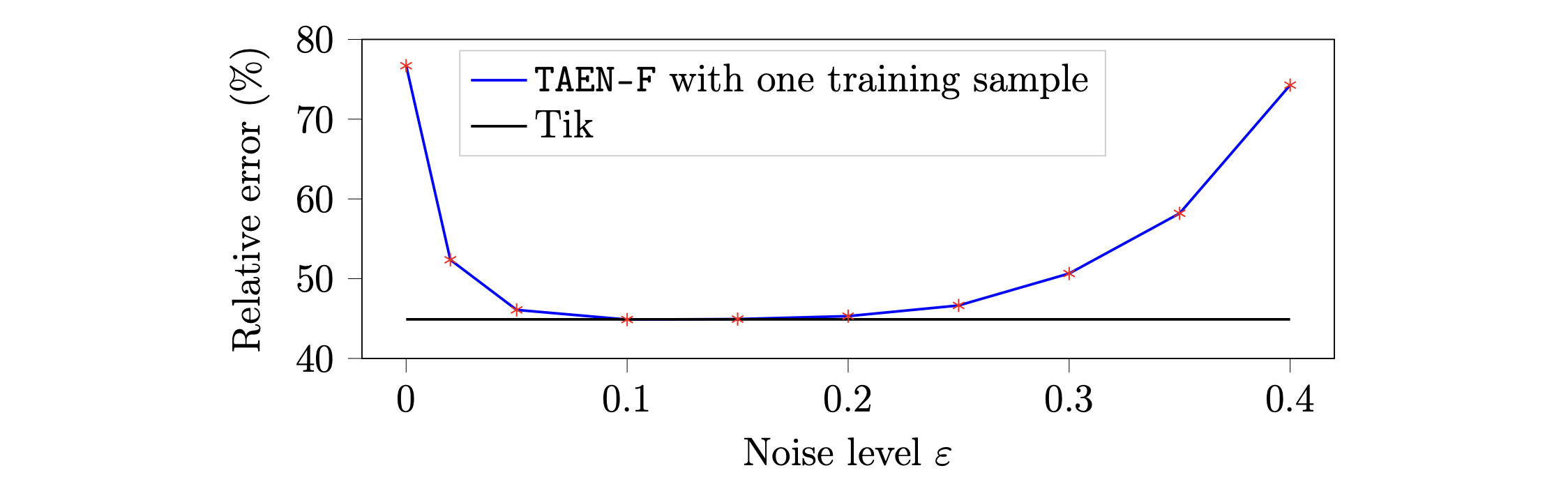

TAENfull robustness to a wide range of noise levels.

We further investigate the robustness of TAENfull across varying noise levels using a single training sample.

TAENfull robustness to arbitrary single-sample.

In this section, we investigate the robustness of the TAENfull framework to one arbitrarily chosen sample for training. To that end, ten independent training instances are conducted, each utilizing a single sample randomly selected from a pool of 100 training samples.

Problem 2: 2D Navier-Stokes Equations

The vorticity form of 2D Navier–Stokes equation for viscous and incompressible fluid is written as

\[\begin{aligned} \partial_t \omega(x,t) + v(x,t) \cdot \nabla \omega(x,t) & = \nu \Delta \omega(x,t) + f(x), & \quad x \in (0,1)^2, t \in (0, T], \\ \nabla \cdot v(x,t) & = 0, & \quad x \in (0,1)^2, t \in (0, T], \\ \omega(x,0) & = u(x), & \quad x \in (0,1)^2, \end{aligned}\]where \(v \in (0,1)^2 \times (0, T]\) denotes the velocity field, \(\omega = \nabla \times v\) represents the vorticity, and \(u\) defines the initial vorticity which is the parameter of interest. The forcing function is specified as \(f(x) = 0.1 (\sin(2 \pi (x_1 + x_2)) + \cos(2 \pi (x_1 + x_2)))\), with viscosity coefficient \(\nu = 10^{-3}\). The computational domain is discretized using a uniform \(32 \times 32\) mesh in space, while the temporal domain \(t \in (0, 10]\) is partitioned into 1000 uniform time steps with \(\Delta t = 10^{-2}\). The inverse problem aims to reconstruct the initial vorticity field \(u\) from vorticity measurements \(\mathbf{y}\) collected at 20 random spatial locations from the vorticity field \(\omega\) at the final time \(T = 10\).

| Approach | Inverse (%) (1 sample) | Forward (1 sample) | Inverse (%) (100 samples) | Forward (100 samples) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure POP | 156.99 | 2.99×10⁻¹ | 72.22 | 6.72×10⁻² |

| Pure OPO | 103.94 | 5.60 | 40.20 | 5.94×10⁻¹ |

| mcPOP | 161.48 | 2.99×10⁻¹ | 76.33 | 6.72×10⁻² |

| mcOPO | 46.43 | 5.15×10⁻¹ | 27.29 | 2.20×10⁻³ |

| mcOPOfull | 46.43 | 3.79×10⁻¹ | 27.29 | 2.12×10⁻³ |

| TAEN | 25.68 | 2.14×10⁻³ | 24.54 | 1.49×10⁻³ |

| TAENfull | 25.68 | 2.10×10⁻³ | 24.54 | 1.45×10⁻³ |

| Tikhonov | 22.71 | - | 22.71 | - |

Table 2: 2D Navier--Stokes equation. Average relative error for inverse solutions and PtO/forward solutions obtained by all approaches trained with \(\{1,100\}\) training samples. The model-constrained approaches are more accurate for both inverse (comparable to the Tikhonov—Tik—approach) and forward solution, and within the model-constrained approaches, TAEN and TAENfull are the most accurate ones: in fact one training sample is sufficient for these two methods. When trained on a single sample, TAEN and TAENfull achieve the lowest average relative error of 25.68% (closest to the gold-standard Tikhonov regularization solution with 22.71% error) for inverse solutions among all approaches. Similarly, their PtO/forward solutions demonstrate superior accuracy with average relative errors of \(2.14 \times 10^{-3}\) and \(2.10 \times 10^{-3}\), respectively. This generalization accuracy is owing to the combination of data randomization and forward solver model-constrained terms. The mcOPO and mcOPOfull approaches come in second with regard to the accuracy for inverse solutions, with a relative error of 46.43%. This reduced accuracy (relatively to TAEN and TAENfull) stems from a strong bias toward the single training sample, despite the forward solver constraint. mcPOP, Pure OPO, and Pure POP exhibit significantly higher average relative errors of 161.48%, 103.94%, and 156.99% respectively for inverse solutions. These poor results are expected for Pure OPO and Pure POP due to their purely data-driven nature, thus limiting generalization. For mcPOP, the inaccurate encoder (learned PtO map) propagates errors to the decoder training, resulting in imprecise inverse surrogate models. For PtO/forward solutions, Pure POP, Pure OPO, mcPOP, mcOPO, and mcOPOfull fail to produce accurate surrogate models, again due to overfitting to the single training sample despite forward solver regularization. When we increase the number of training samples to 100, and thus providing more information about the problem under consideration, significant accuracy improvements are observed for all approaches for both inverse and PtO/forward surrogate models. TAEN and TAENfull approaches maintain the best performance, achieving average relative errors of 24.54% for inverse solutions compared to the Tikhonov (Tik) method with of 22.71%. Their PtO/forward solutions exhibit good accuracy with average relative errors of \(1.49 \times 10^{-3}\) and \(1.45 \times 10^{-3}\), respectively. The average relative error of the inverse solution obtained by mcOPO and mcOPOfull is \(27.29\%\), which is the second best among all approaches. The relative error of the PtO/forward solution obtained by mcOPO and mcOPOfull is \(2.20 \times 10^{-3}\) and \(2.12 \times 10^{-3}\), respectively, which is almost as good as TAEN and TAENfull. This indicates the roles of model-constrained terms in reducing the overfitting effect when sufficient training data is provided. In contrast, Pure POP and mcPOP show substantially higher relative errors of 72.22% and 76.33%, respectively, for inverse solutions. These high errors stem from inaccuracies in their pre-trained PtO map (encoder), consistent with observations from the single-sample training scenario. Meanwhile, Pure OPO framework shows improved inverse solution accuracy with a relative error of 40.20%, yet remains less accurate than the model-constrained approaches (mcOPO, mcOPOfull, TAEN, and TAENfull). This reduced performance is consistent with the error analysis for linear problems. Moreover, Pure OPO's PtO solution accuracy remains notably poor (\(5.94 \times 10^{-1}\)) despite the richer training dataset with 100 data pairs, reflecting the inherent PtO mapping errors.

Generating train and test data sets.

To generate data pairs of \((u, \omega)\), we draw samples of \(u(x)\) using the truncated Karhunen-Loève expansion

\[u(x) = \sum_{i=1}^{24} \sqrt{\lambda_i} \, \boldsymbol{\phi}_i(x) \, z_i,\]where \(z_i \sim \mathcal{N}(0, 1), i = 1, \ldots, 24\), and \((\lambda_i, \boldsymbol{\phi}_i)\) are eigenpairs obtained by the eigendecomposition of the covariance operator \(7^{\frac{3}{2}} (-\Delta + 49 \mathbf{I})^{-2.5}\) with periodic boundary conditions. Next, we discretize the initial vorticity \(u(x)\), denoted as \(\mathbf{u}\), and we solve the Navier-Stokes equation by the stream-function formulation with a pseudospectral method to obtain a discrete representation \(\mathbf{y}_{\text{full}}\) of \(\omega(x,t)\) at time \(t = 10\). The observation data \(\mathbf{y}\) consists of the vorticity field \(\mathbf{y}_{\text{full}}\) at \(T = 10\) at 20 randomly distributed observational locations, with the subsequent addition of \(\delta = 2\%\) Gaussian noise. Two distinct datasets are generated: a training set comprising 100 independent samples and a test set containing 500 samples.

Learned inverse and PtO/forward maps accuracy.

Following the same procedure used for the 2D heat equation, encoder and decoder networks are trained sequentially for two cases: using a single training sample pair (shown in Figure 9) and using 100 training sample pairs. For mcOPO, mcOPOfull, TAEN and TAENfull approaches, randomization is performed at each epoch with noise level \(\epsilon = 25\%\).

| Approach |

1 training sample mean |

1 training sample std |

100 training samples mean |

100 training samples std |

| Pure POP |

|

|

|

|

| Pure OPO |

|

|

|

|

| mcPOP |

|

|

|

|

| mcOPO / mcOPOfull |

|

|

|

|

| TAEN / TAENfull |

|

|

|

|

| Tik |

|

|

| Pure POP / mcPOP | Pure OPO | mcOPO | mcOPOfull | TAEN | TAENfull | |

| 1 sample |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 100 samples |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 training sample mean |

1 training sample std |

100 training samples mean |

100 training samples std |

|

| mcOPOfull |

|

|

|

|

| TAENfull |

|

|

|

|

| $$\mathbf{u}_\text{Tik}$$ | $$\mathbf{u}_{\text{TAENfull}}$$ | $$\mathbf{u}_\text{True}$$ | $$\mathbf{y}_{\text{TAENfull}}$$ |

|

|

|

|

|

| $$\|\mathbf{u}_\text{Tik} - \mathbf{u}_\text{True}\|$$ | $$\|\mathbf{u}_{\text{TAENfull}} - \mathbf{u}_\text{True}\|$$ | $$\mathbf{y}_\text{True}$$ | $$\|\mathbf{y}_{\text{TAENfull}} - \mathbf{y}_\text{True}\|$$ |

|

|

|

|

|

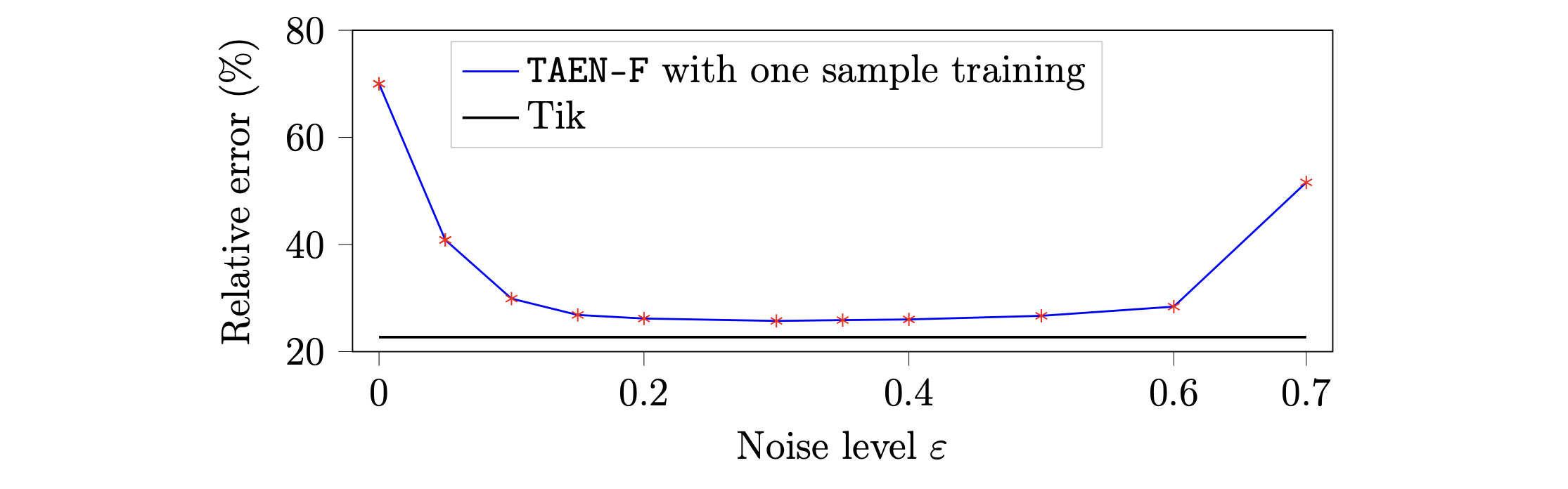

TAENfull robustness to a wide range of noise levels.

A survey of TAENfull trained with one training sample over a wide range of noise levels is shown in Figure 14.

TAENfull robustness to arbitrary single-sample.

The robustness of TAENfull to an arbitrary one-training sample is examined. To be more specific, we randomly pick 12 samples out of 100 training sample data sets.

Training Cost and Speedup with Deep Learning Solutions

The training costs for the case of \(n_t = 100\) randomized training samples for heat equation and Navier–Stokes equations are presented in Table 3. It can be observed that the heat equation requires a small amount of training time, about 2 hours, while the corresponding time for the Navier-Stokes equations is about 16 hours. It should be noted that executing the forward map and the backpropagation constitutes the majority of the training cost.

Table 3 also provides information on the computational cost of reconstructing PoIs given an unseen test observation sample and solving for PDE solutions given an unseen PoI sample. Specifically, for inverse solutions, we use the classical Tikhonov (TIK) regularization technique and our proposed deep learning approach TAENfull using the encoder network. In contrast, we use numerical methods and TAENfull decoder for predicting (forward) PDE solutions.

| Heat equation | Navier--Stokes | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Training Encoder + Training Decoder (hours) | 2 | 16 | |

| Test/Inference (second) | Inverse (Encoder) | $$2.74 \times 10^{-4}$$ | $$2.93 \times 10^{-4}$$ |

| Forward (Decoder) | $$2.86 \times 10^{-4}$$ | $$3.06 \times 10^{-4}$$ | |

| Numerical solvers (second) | Inverse (Tikhonov) | $$4.36 \times 10^{-2}$$ | 7.26 |

| Forward | $$3.01 \times 10^{-2}$$ | 0.38 | |

| Speed up | Inverse | 159 | 24,785 |

| Forward | 105 | 1,241 | |

Table 3: Training cost and computational speed. The training cost (measured in hours) for the case of \(n_t = 100\) randomized training samples for the heat and Navier--Stokes equations. The computational time (measured in seconds) for forward and inverse solutions using TAENfull and numerical solvers, and the speed-up of TAENfull (the fourth row) relative to numerical solvers using NVIDIA A100 GPUs on Lonestar6 at the Texas Advanced Computing Center (TACC).